A 55-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and prior cervical conisation, with no other significant comorbidities, presented with progressively worsening dyspnea. Over several days she developed a dry, irritating cough unresponsive to antitussive therapy and reported fever up to 38 °C. Her dyspnea progressed from NYHA class II toI II–IV. Pulmonary embolism was excluded. Initial evaluation suggested new-onset heart failure. ECG demonstrated inferior wall abnormalities, and bedside echocardiography revealed severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with diffuse hypokinesis.

The patient smoked 10–15 cigarettes daily, drank alcohol occasionally, and denied illicit drug use.

She was transferred to our center with a working diagnosis of myocarditis.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

Clinical examination

• Dyspnea at rest with cough worsening in the supine position

• Heart rate 151 bpm, blood pressure 97/57 mmHg

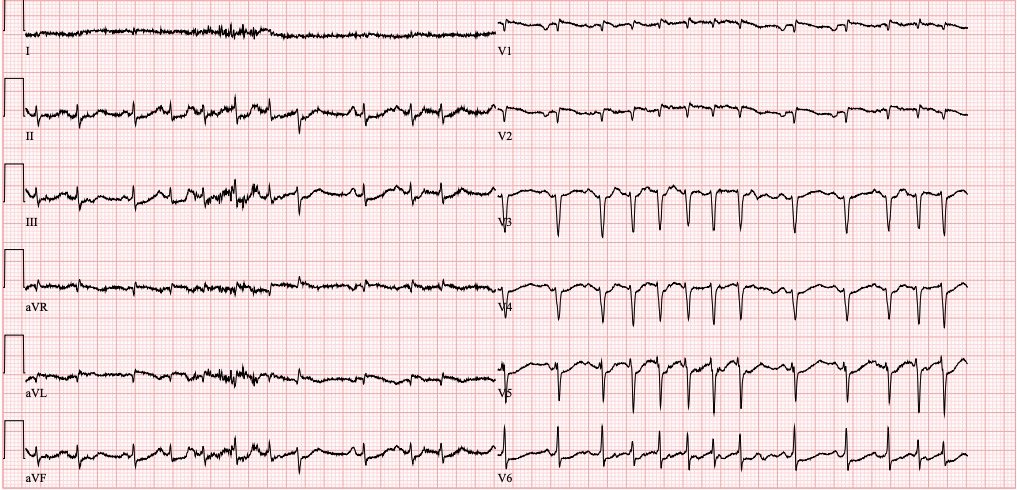

• Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response

• Oxygen saturation 91% on room air

• Basal attenuation of breath sounds with bilateral crackles

• No peripheral edema

ECG on admission

Laboratory Findings

Renal function was preserved with no abnormalities in the mineralogram. Liver biochemistry showed mild enzyme elevation, including alkaline phosphatase 2.46 µkat/L (reference 0.58–1.75 µkat/L), AST 0.77 µkat/L (0.17–0.75 µkat/L), and ALT 0.57 µkat/L (0.17–1.17 µkat/L), with normal total bilirubin 10.8 µmol/L (3.4–20.0 µmol/L).

Inflammatory markers were markedly elevated, with CRP 134 mg/L (0–5 mg/L), while procalcitonin remained low at 0.10 µg/L (0–0.5 µg/L).

Cardiac biomarkers revealed myocardial injury, with high-sensitivity troponin T 491 ng/L showing a dynamic rise to 654 ng/L (0–9 ng/L) and BNP 2106 ng/L (10–155 ng/L).

Complete blood count demonstrated leukocytosis 15.1 ×10⁹/L (4–10 ×10⁹/L), normal hemoglobin 125 g/L (120–160 g/L), and normal platelet count 248 ×10⁹/L (150–400 ×10⁹/L).

Coagulation tests showed only mild prolongation of INR and aPTT.

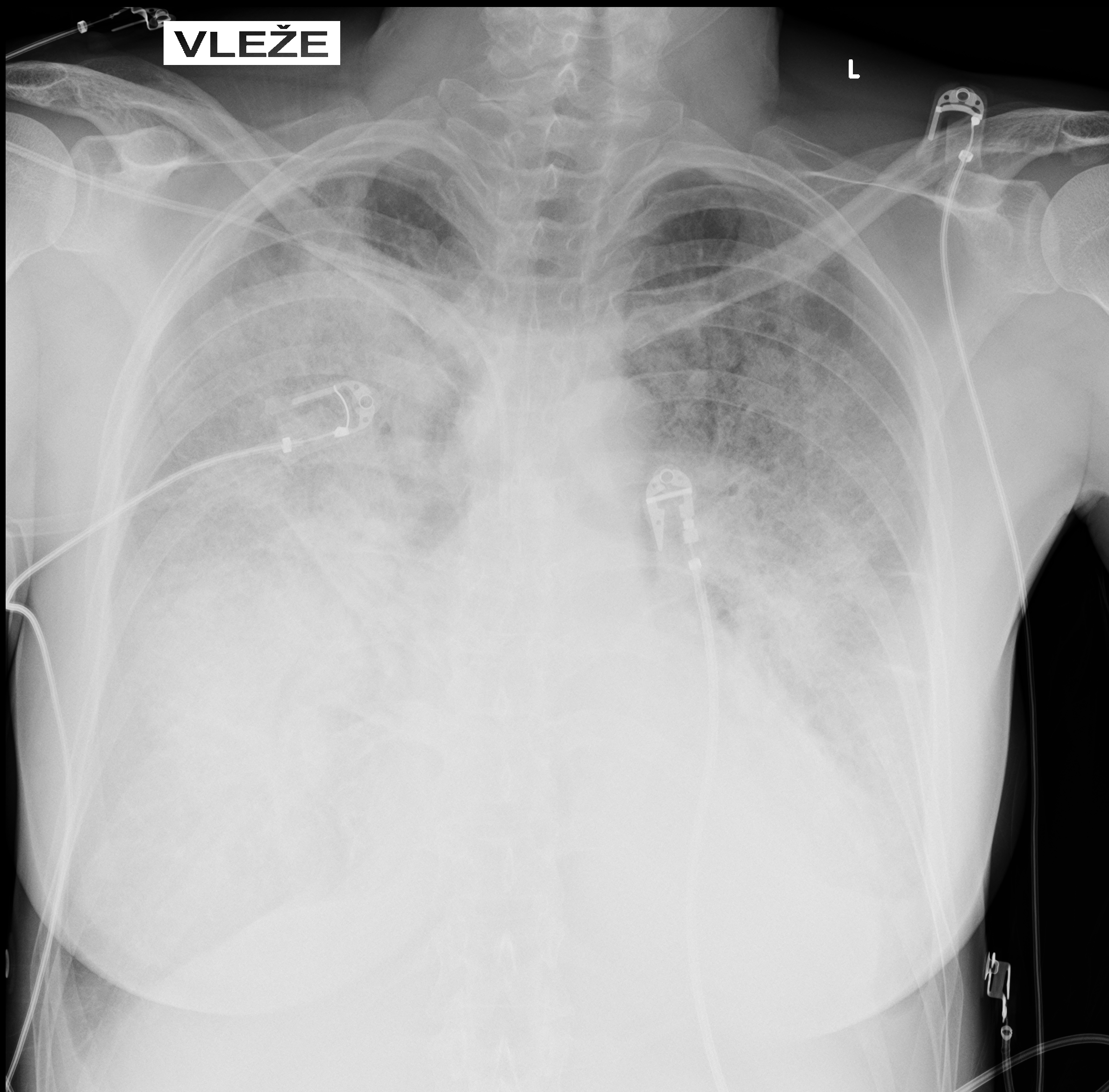

Imaging

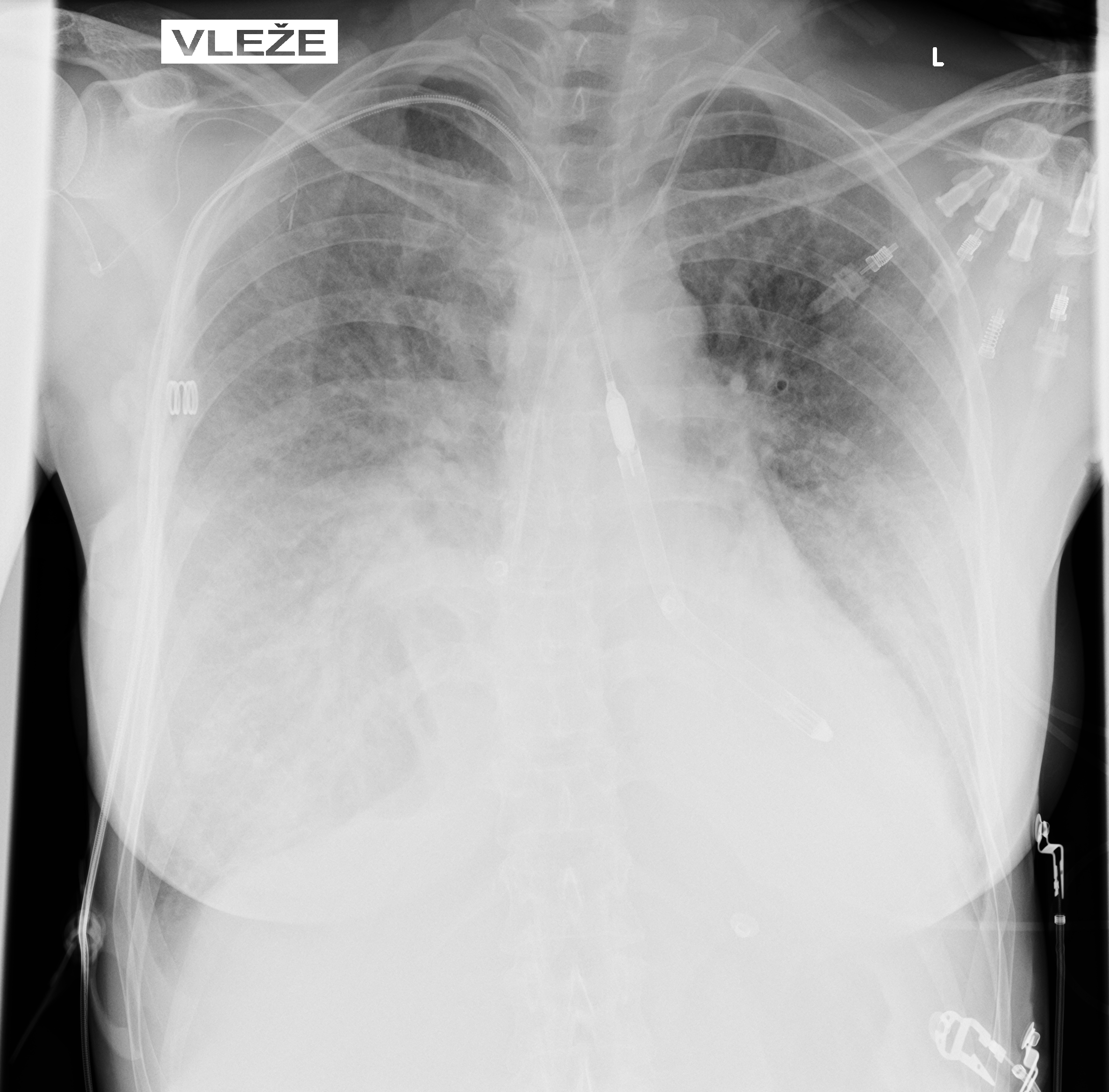

Chest X-ray on admission:

Markedly reduced bilateral transparency with perihilar opacities suggestive of pulmonary edema vs. early ARDS. Possible right-sided consolidation. Small pleural effusions not excluded. Cardiac silhouette enlarged.

Echocardiography on admission:

Transthoracic Echocardiography on Admission

• Mildly dilated left ventricle (LVEDD 55 mm)

• Severe global hypokinesis

• Left ventricular ejection fraction 20–25%

• Mild mitral regurgitation

• Right ventricle normal in size and systolic function

Fig. 3: ECHO on admission, severe global hypokinesis, mild mitral regurgitation - A4C

Lung ultrasound:

• Bilateral B-lines

• Small pleural effusions

• Findings consistent with pulmonary congestion

Coronary angiography

Normal coronary arteries except for minor irregularities in the proximal LAD. Right coronary artery hypoplastic due to left dominance.

WORKING DIAGNOSIS

Fulminant inflammatory myopericardial syndrome – Suspected giant-cell myocarditis (GCM)

Given rapid clinical deterioration, severe LV dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and unobstructed coronaries, urgent endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) was performed on day 1.

Preliminary pathology strongly suggested giant-cell myocarditis.

Early Management

The patient required low-dose norepinephrine to maintain MAP (mean arterial pressure), but lactate remained normal (1.8 mmol/L). No malignant ventricular arrhythmias occurred beyond paroxysmal AF with RVR.

Diagnostic workup prior to immunosuppression:

A comprehensive infectious and immunologic evaluation was performed and included:

• Antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, interleukin-6

• Viral serology for CMV, EBV, HSV, VZV, HBV, HCV, and HIV

• CMV PCR testing

• Stool cultures including Clostridioides difficile

• Sputum and blood cultures

• Urine pneumococcal antigen

• Lymphocyte subset analysis

• Immunoglobulins and immunoelectrophoresis prior to IVIG administration

• Bronchoalveolar lavage was proposed to exclude pulmonary infection

Immunosuppressive Therapy

Once active infection was reasonably excluded, combination immunosuppressive therapy was initiated.

Corticosteroids

• Methylprednisolone 1 g intravenously daily for 3 consecutive days

• Followed by oral prednisone 40–60 mg daily with gradual taper

Adjunctive Immunosuppression

• Intravenous immunoglobulin 0.5 g/kg administered over 24–48 hours

• Antithymocyte globulin at a dose of 0.5–1 mg/kg

Calcineurin Inhibitor

• Tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily

• Target trough concentration 10–15 ng/mL

Antimetabolite

• Mycophenolate mofetil 500–1000 mg twice daily

• Added after definitive histological confirmation

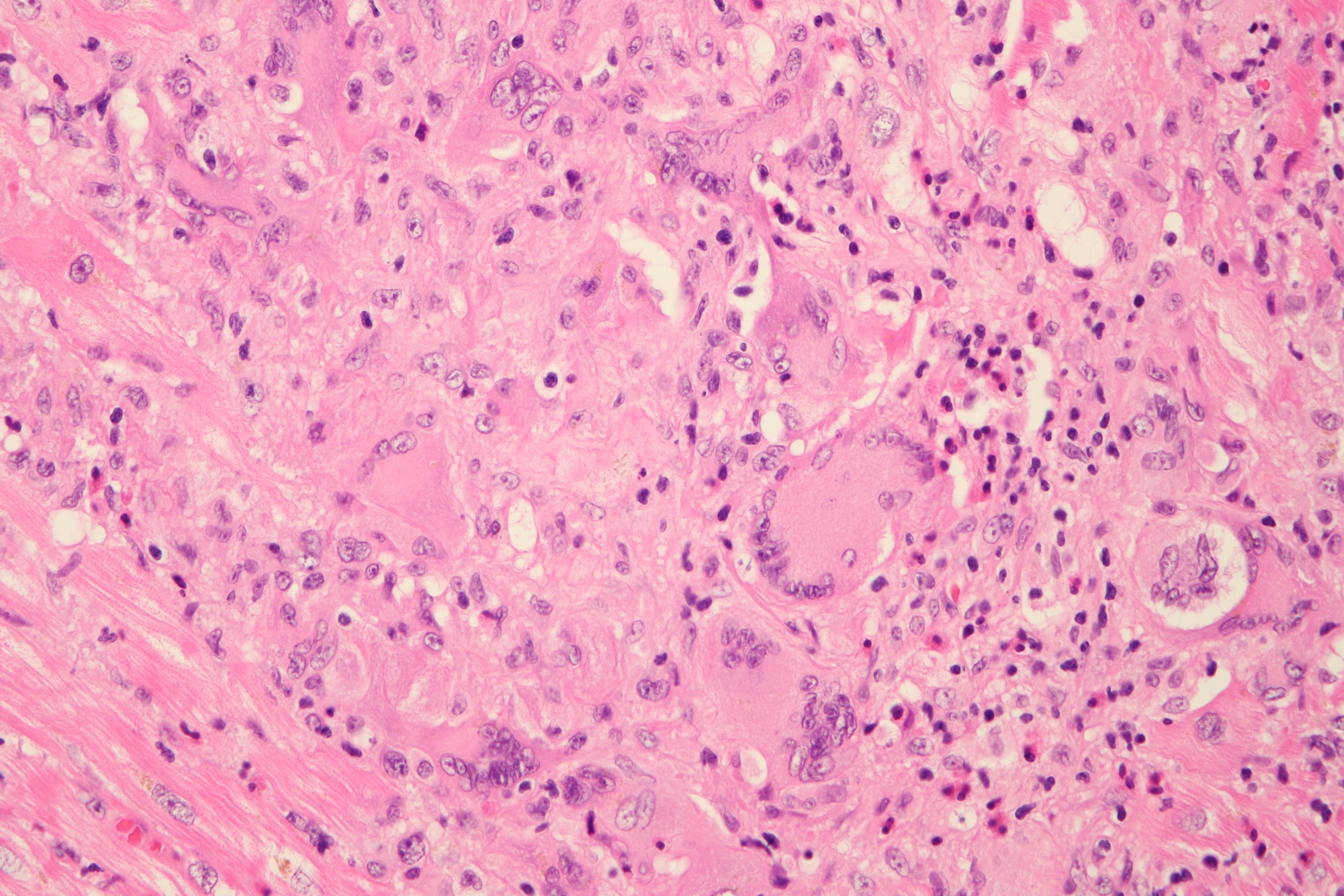

Pathology

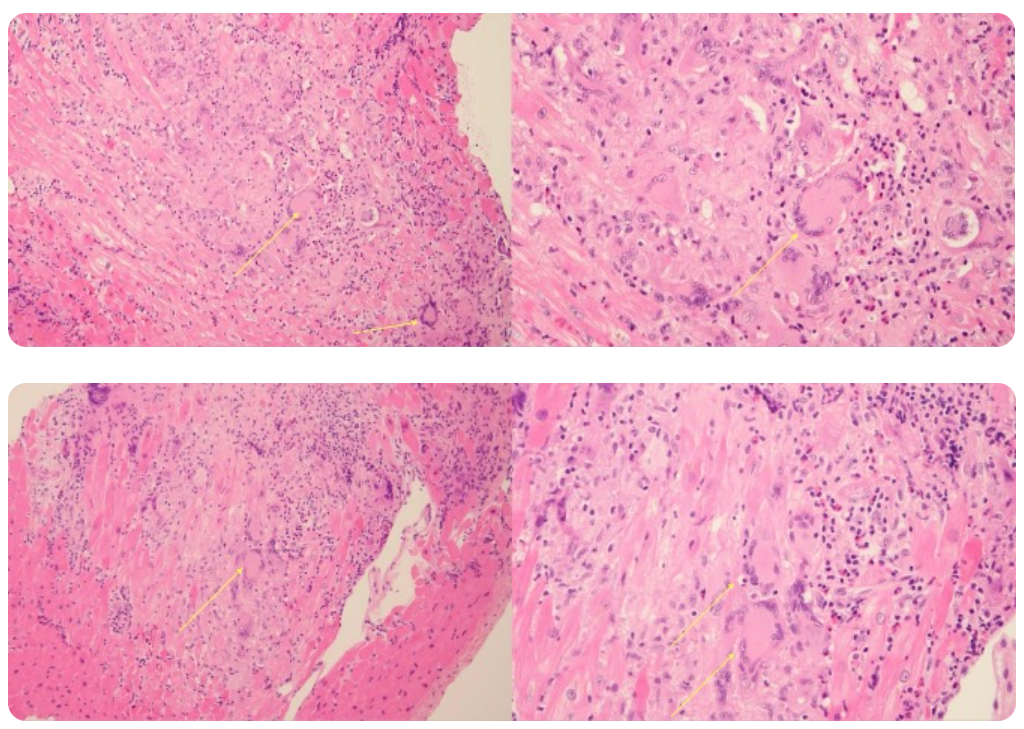

Endomyocardial biopsy revealed:

• Necrotizing myocarditis

• Diffuse cardiomyocyte necrosis

• Mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils

• Multiple multinucleated giant cells

These findings confirmed the diagnosis of giant-cell myocarditis.

Fig. 8: EMB findings (multinucleated cells are marked with yellow arrows) Pathology has now confirmed the suspected diagnosis.

Mechanical circulatory support

Due to persistent severe LV dysfunction and risk of cardiogenic shock, Impella 5.5 was implanted on day 3 for LVunloading.

Correct position was assessed by TEE and CXR

CLINICAL COURSE

In hospital summary:

During hospitalization, the patient’s clinical condition gradually improved. By day 24, she tolerated P-1 support at 0.8 L/min, allowing successful discontinuation of mechanical circulatory support. She was subsequently transferred to a standard ward and, after several days, discharged home on ongoing immunosuppressive therapy with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil, together with tapering corticosteroids. Long-term, likely lifelong, immunosuppressive therapy is anticipated.

The use of the Impella 5.5 device enabled early initiation and rapid up-titration of guideline-directed heart failure therapy, which was subsequently continued and optimized in the heart failure outpatient clinic.

Echocardiography Before Discharge

• Left ventricular ejection fraction improved to 50–55%

• Borderline right ventricular systolic function

DISCUSSION: Giant-Cell Myocarditis – Diagnosis and Management

1. Pathology and Pathogenesis

GCM is characterized by:

• Mixed inflammatory infiltrate with T-lymphocytes and macrophages

• Abundant multinucleated giant cells

• Confluent myocyte necrosis

• Eosinophils are often present

Conditions associated with GCM:

• Autoimmune diseases (UC, Crohn’s, polymyositis, myasthenia gravis)

• Thymoma or other malignancies

• Drug hypersensitivity (antiepileptics)

2. Clinical Presentation

Historical and contemporary cohorts show:

• Acute heart failure: 31–75%

• Advanced AV block: 5–30%

• Sustained ventricular arrhythmias: 14–22%

• ACS-like presentation: ~13%

• Cardiac arrest: 4–8%

Presentation is often fulminant, with rapid deterioration requiring urgent intervention.

3. Diagnosis

Essential steps

• Exclude ischemia (angiography)

• Identify severe biventricular or isolated LV failure

• Rule out systemic infection prior to immunosuppression

• Obtain endomyocardial biopsy early

Role of biopsy

• EMB is mandatory for suspected GCM.

• Delay in biopsy correlates with increased mortality.

Role of CMR

• Helpful when stable, showing myocardial edema

• LGE in non-ischemic distribution

• But not diagnostic.

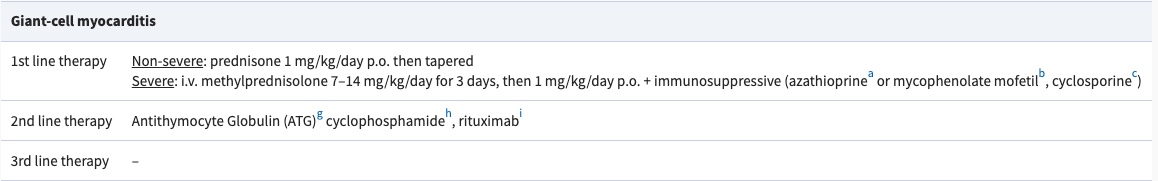

4. Treatment Principles

A. Combined immunosuppression

Steroid monotherapy is insufficient.

Recommended (ESC 2025):

• High-dose steroids

• Calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus or cyclosporine)

• Antimetabolite (MMF or azathioprine)

• Consider ATG and (+/− IVIG in fulminant cases)

Intravenous immunoglobulins in GCM:

Evidence supporting IVIG in GCM is limited, but experimental models demonstrate reduced myocardial necrosis and inflammatory activity with high-dose IVIG. Human data consist mainly of case reports in which IVIG was used as part of combination immunosuppression in fulminant disease. Accordingly, IVIG is considered a potential adjunct in selected patients with severe or rapidly progressive GCM, though it is not established as standard therapy.

Pathophysiology of IVIG and ATG:

High-dose IVIG (usually ~1–2 g/kg total dose) is pooled human IgG with broad immunomodulatory effects rather than simple “replacement”. Key mechanisms:

• Fc receptor blockade = Saturates activating Fcγ receptors on macrophages and dendritic cells, shifting the balance toward inhibitory FcγRIIb → dampens phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and pro-inflammatory signalling.

• Neutralisation of autoantibodies & complement

• Anti-idiotype antibodies in IVIG can bind and neutralize pathogenic autoantibodies.

• IVIG can scavenge activated complement fragments and prevent membrane attack complex formation on cardiomyocytes.

• Cytokine and cell-signalling modulation

• Down-regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6),

• Up-regulates anti-inflammatory mediators and can expand regulatory T cells.

• Effects specific to autoimmune GCM models

• In autoimmune GCM rats, IVIG reduced myocardial giant-cell inflammation, suppressed dendritic cell activation, and improved LV function, consistent with Fc-receptor–mediated inhibitory action.

ATG

Rabbit antithymocyte globulin (rATG, e.g. Thymoglobulin) is a polyclonal antibody preparation against human T-cell antigens, used mainly in transplant medicine and severe T-cell–mediated diseases.

• Broad T-cell depletion

• Antibodies bind multiple T-cell surface targets (CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, etc.).

• Causes T-cell death via:

• Complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC)

• Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)

• Induction of apoptosis (activation-induced cell death).

• Modulation of immune networks

• Down-modulates adhesion and costimulatory molecules (e.g. CD11a, CD18, HLA-DR), impairing T-cell activation and homing.

• Affects B cells, plasma cells, NK cells and dendritic cells to a lesser extent.

• Can relatively enrich for regulatory T cells over time, contributing to a more tolerogenic immune profile.

B. Mechanical circulatory support

GCM often requires mechanical circulatory support either to bridge the patient through the acute phase or to bridge to heart transplantation.

• Microaxial pump as LV unloading (e.g. Impella)

• VA-ECMO (circulatory collapse)

• Durable LVAD as bridge to transplant

C. Arrhythmia management

Frequent arrhythmias often require:

• Antiarrhytmic drugs

• Cardioversion/Defibrillation

• Temporary pacing

D. Anticoagulation

Recommended if GCM is associated with:

• Atrial fibrillation

• Severe LV dysfunction

• Intracardiac thrombus present or risk of forming

E. Infection prophylaxis

Due to high-dose, multimodal immunosuppression.

• In clinical practice, valganciclovir and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole are most commonly used.

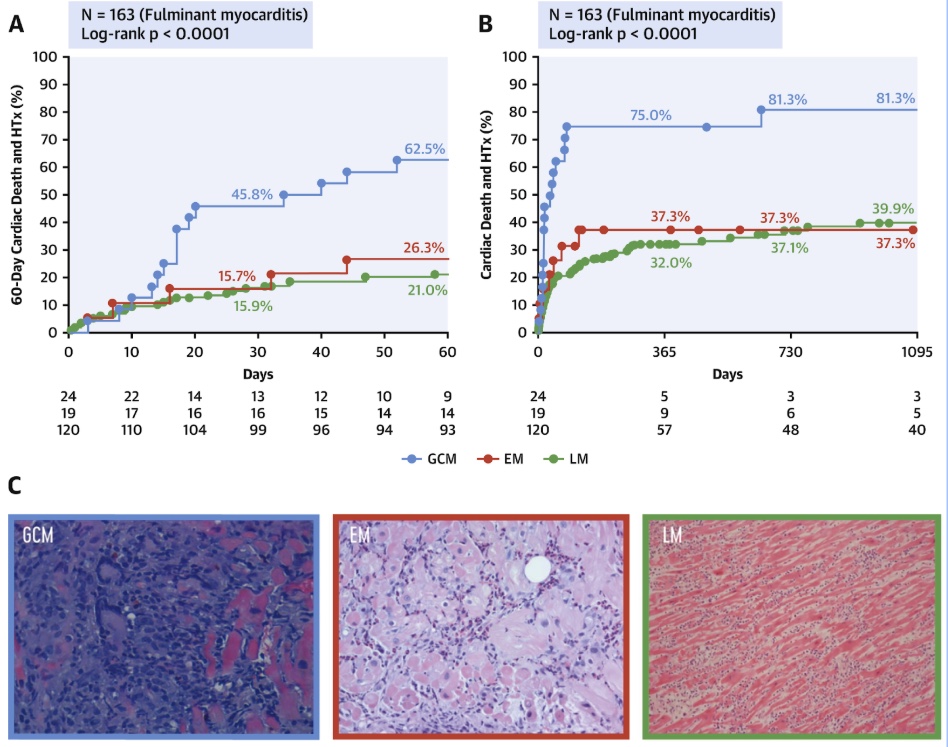

5. Prognosis

GCM has significantly worse mid- and long-term prognosis compared to other types of fulminant myocarditis - eosinophilic and lymphocytic myocarditis.

The authors would like to sincerely thank Assoc. prof. Ondřej Fabián, M.D., Ph.D., for his kind assistance, expertise, detailed description, and for providing the imaging documentation from the endomyocardial biopsy.

Also, a big thank you belongs to Cardiology and Cardiosurgery Departments Teams from IKEM Prague.

References:

1. ESC Guidelines for Myocarditis and Pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2025; doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf192.

2. Kandolin R, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of giant-cell myocarditis. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(1):15–22.

3. Ammirati E, Veronese G, Brambatti M, Merlo M, Cipriani M, Potena L, Sormani P, Aoki T, Sugimura K, Sawamura A, Okumura T, Pinney S, Hong K, Shah P, Braun Ö, Van de Heyning CM, Montero S, Petrella D, Huang F, Schmidt M, Raineri C, Lala A, Varrenti M, Foà A, Leone O, Gentile P, Artico J, Agostini V, Patel R, Garascia A, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Hirose K, Isotani A, Murohara T, Arita Y, Sionis A, Fabris E, Hashem S, Garcia-Hernando V, Oliva F, Greenberg B, Shimokawa H, Sinagra G, Adler ED, Frigerio M, Camici PG. Fulminant Versus Acute Nonfulminant Myocarditis in Patients With Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jul 23;74(3):299-311. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.063. PMID: 31319912.

4. Bang V, Ganatra S, Shah SP, Dani SS, Neilan TG, Thavendiranathan P, Resnic FS, Piemonte TC, Barac A, Patel R, Sharma A, Parikh R, Chaudhry GM, Vesely M, Hayek SS, Leja M, Venesy D, Patten R, Lenihan D, Nohria A, Cooper LT. Management of Patients With Giant Cell Myocarditis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Mar 2;77(8):1122-1134. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.074. PMID: 33632487.

5. Cooper LT Jr. Giant cell myocarditis: diagnosis and treatment. Herz. 2000 May;25(3):291-8. doi: 10.1007/s000590050023. PMID: 10904855.

6. Zhang W, Guo T. A giant and rapid myocardial remodeling due to fatal giant cell myocarditis: a case report. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025 Feb 26;12:1488503. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1488503. PMID: 40078460; PMCID: PMC11897473.

7. Ekström K, Räisänen-Sokolowski A, Lehtonen J, Kupari M. Long-term outcome and its predictors in giant cell myocarditis. Letter regarding the article 'Long-term outcome and its predictors in giant cell myocarditis'. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 Jul;22(7):1283-1284. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1953. Epub 2020 Jul 28. PMID: 32613726.

8. Kato S, Morimoto S, Hiramitsu S, Uemura A, Ohtsuki M, Kato Y, Miyagishima K, Mori N, Hishida H. Successful high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for a patient with fulminant myocarditis. Heart Vessels. 2007 Jan;22(1):48-51. doi: 10.1007/s00380-006-0923-3. Epub 2007 Jan 26. PMID: 17285446.

9. Funaki T, Saji M, Murai T, Higuchi R, Nanasato M, Isobe M. Combination Immunosuppressive Therapy for Giant Cell Myocarditis. Intern Med. 2022 Oct 1;61(19):2895-2898. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9112-21. Epub 2022 Mar 5. PMID: 35249924; PMCID: PMC9593153.

10. Laufs H, Nigrovic PA, Schneider LC, Oettgen H, Del NP, Moskowitz IP, Blume E, Perez-Atayde AR. Giant cell myocarditis in a 12-year-old girl with common variable immunodeficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002 Jan;77(1):92-6. doi: 10.4065/77.1.92. PMID: 11795251.

You Might Also Like

Cardiogenic shock due to Giant Cell Myocarditis

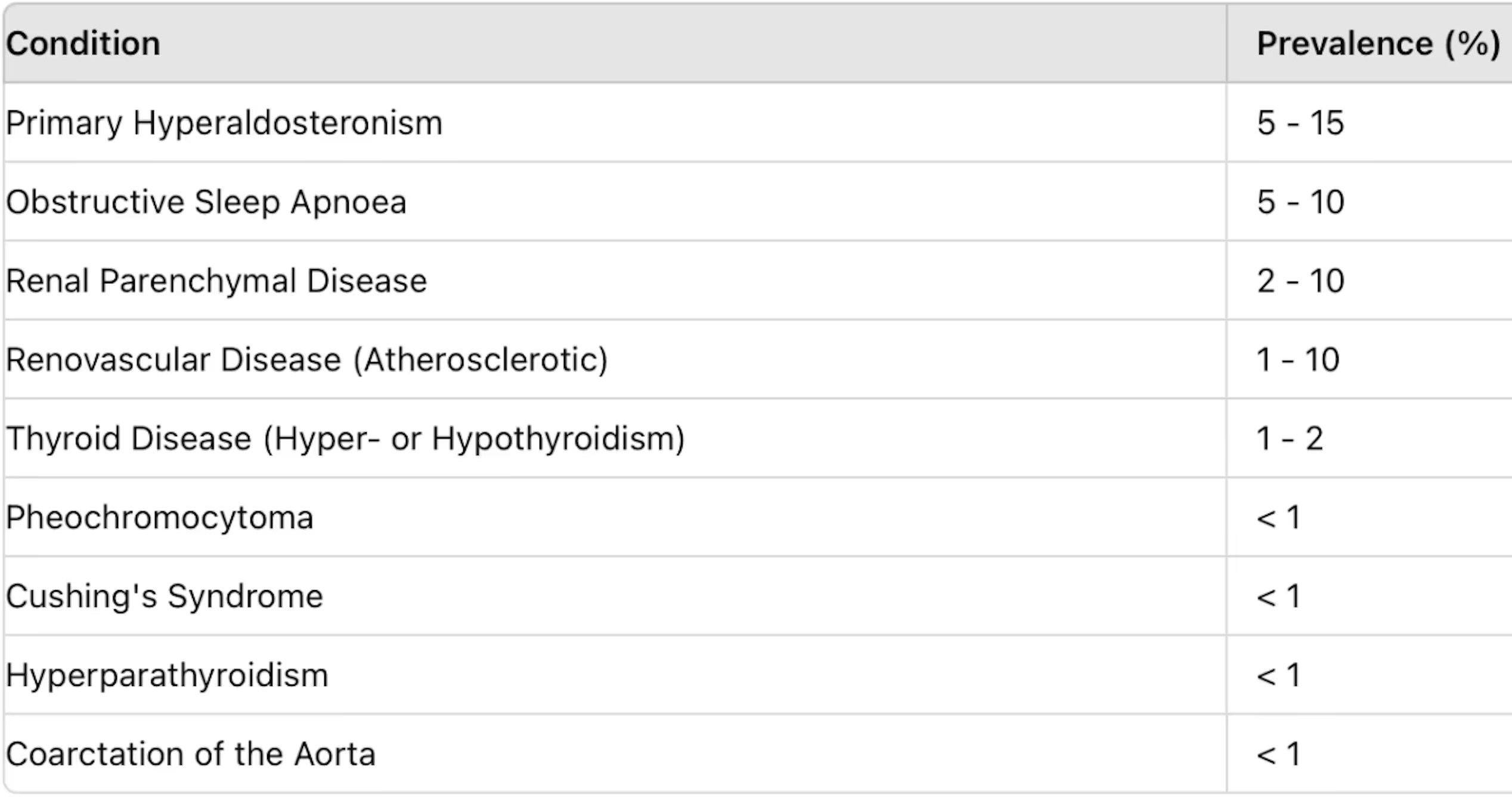

Secondary hypertension